One's life should be so arranged that it remains a mystery to other people, so that those who know one best in fact know one as little as anyone else, only from a slightly nearer vantage point.

Fernando Pessoa Tweet

Adam’s life is a mystery to me. As an adult, I didn’t know him well from any vantage point. For a few short years, Adam and I were friends at school. We were small boys years away from reaching our explosive and electric teenage years, lived in the early 70s, that may have steered him toward his own destiny and that left me confused and dazed for decades. Whoever I remember him to be in those childhood years is, I know, as far from the Adam of his adult life as it is possible to get.

Two small English boys marooned in an Australian boarding school, that was the starting point for friendship. There was a strange cognitive dissonance to this. The boarding school was a small island of almost extreme anglophilia surrounded by a vast ocean of australiana.

It was by design, ‘England’: faux-Tudor architecture, oak studded parks, groomed playing fields, Church of England chapel with obligatory stained glass windows donated by old boys, cassocked choir boys, and the compulsory rugby and cricket. All of the witheringly cruel and humiliating English public school rituals and punishments had also been imported. A shrine to the tatty England of Empire and public schools. To the forging of young bodies and minds into colonial approximations of the English gentleman – already, in the 1960s a dated and almost comic cliché . England meticulously recreated in the dry dusty landscape of a country on the other side of the globe.

Just outside the gates of this speck of England, Australia sweated and strained under its oppressive heat. Bushfires raged through eucalyptus forests. Giant bull ants stuck their painful stingers into your pink fleshy parts, you roasted under that fierce sun, flies buzzed around your head crawled into your mouth, and most Australians thought of their English cousins, especially the wealthy and privately educated, as, well … pompous, pretentious twats.

School photo circa 1964. Adam (second from top row) and the author (second from bottom row)

A cohort of pupils, hating their own imprisonment with its heavy-handed dosing of anglo-syrup, ridiculed, bullied and generally came down hard upon Adam and me, unwilling representatives, as we were, of that utopia none of them had signed up.

In these schools, as the studies on ‘privileged abandonment‘ have shown: some harden, some break and almost none come out emotionally unscathed.

Adam and I huddled together in our inescapable ‘englishness’ and became friends. Somewhere in there, our parents became friends as well. I have no recollection of what drew the families together – perhaps expats clustering together as they often do in foreign lands. In any case, my family’s connection with Adam’s family lasted no longer than my own with Adam and my memories of this broader, familial connection are almost non-existent.

What I remember of Adam is mainly a face: long, with fleshy lips and large, hooded pale eyes, big ears topped by a burst of sandy hair. Below the face he was gangly. Bony-knees sticking out beneath the school shorts. He was at least a head taller than me although there was no difference in age. We played Beatles songs on our tennis rackets, ran up and down in simulated war games, read Commando comics and, in acts of self-destructive bravado, exaggerated our comically superior English accents to annoy the other boys. Adam loved things military. We made small wooden guns and swords in the school workshop and sold them for bags of sweets collecting a saccharine fortune from miniature AK-47s and replica Lugers. It was no surprise when I read that later in life he had developed a vast knowledge of military history and spent time as a military history proofreader for Cassells.

And that was it. The friendship of small boys thrown together. After a few years, Adam went back to England and I never saw nor heard about him again. Until recently. Now, more than half a century later, I am wondering what the arc of his life must have been.

A few weeks ago I started reading Christopher Hitchens’s Hitch-22. He has been given the prognosis for his cancer and has only months to live:

... I was born to die and this coda must be my attempt to assimilate the narrative to its conclusion

Christopher Hitchens Tweet

And in Prologue with Premonitions, he writes:

And yet here I still am, and resolved to trudge on. Of the many handsome and beautiful visages in the catalogue a distressing number belong to former friends ... who died well before they attained my present age.

Christopher Hitchens Tweet

And here, between ‘friends’ and ‘who died’, I find Adam again. After all those years. Described by Hitchens as ‘the loveable socialite and wastrel and half-brother of Princess Diana – Adam Shand-Kydd’.

I knew that Adam had been the step-brother of Princess Diana and assumed that a life of being partially defined by that relationship must only have been a burden. That addendum to his life did more to obscure than reveal.

Although I’d had a frisson of recognition when I saw his name there was nothing in the description that surprised. That he had been friends with Hitchens made me place Adam in the brilliant literary pool of Hitchens, Amis, Fenton and Barnes. Even if he only occupied a place on the fringe, I found that intriguing. It hinted at Adam’s own intelligence, conversational skills and at the literary path he had chosen to take … or if not take with any deliberation, to wander down in lieu of the many others snaking out before him as he reached adulthood.

One thing I have observed about the alumni of the schools Adam and I went to is that they often inhabit the extremes of the social spectrum: socialites as well as anti-social misanthropes, loveable eccentrics as well as arrogant and entitled bores, productive wunderkinds as well as listless wastrels, realisers of their potential and those who throw their potential to the wind, priests and profligates – with very little in the middle. So Adam, taking the wastrel’s path, if that is a fair description, didn’t surprise. In fact it made me feel closer to him and prompted me to find out a bit more about what his life may have been. More piqued curiosity than investigative journalism. And I have stopped a long way short of filling in anything that I imagine to be a complete portrait of Adam. I became more and more uneasy as I turned up the disparate scraps of information, images and descriptions surrounding his life. The more I found out the less, I was sure, I was getting to know him. Where to stop?

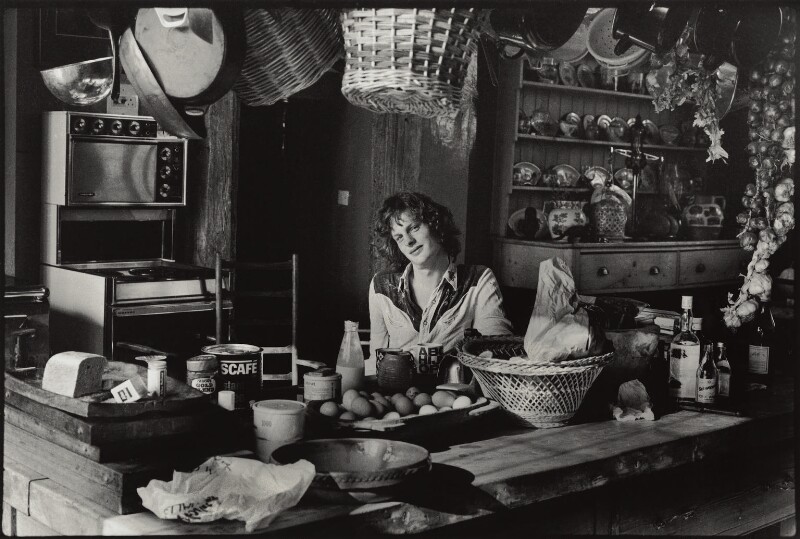

My first search for more information about Adam took me to a 1977 portrait of him taken by Angela Gorgas , now part of the National Portrait Gallery collection. Adam is placed in the centre of the image surrounded by a rustic collection of kitchen utensils, wicker baskets, food, a half finished bottle of milk and some crumpled bags. The 70s cooker and large tin of Nescafé lend the almost Rembrandtian composition a touch of irony that Adam’s direct, quizzical, gaze into the lens emphasises. From the notes on the website I am assuming that this is his mother’s kitchen. Where, the notes say, he ‘seemed most relaxed’. He must be 23 in this photo. I recognise him – he’s improved with age. The lips are still as pronounced and you get an intimation of the long, lanky figure receding under the table. His thick, long, curly hair creates a geometric diamond with the dark shoulder inserts of his shirt. His face is framed by the diamond’s outline. He looks ‘seventies’, sensual and slightly puzzled. He fits Hitchens’s description of a ‘loveable wastrel‘ well.

The photograph of Adam gave me the most immediate and perhaps enduring feeling of who he may have become. The words surrounding him seemed less reliable, more oblique and opaque – hiding more than they revealed whereas I felt, looking at him gazing back from the photo, that there he reveals more than is being hidden.

The most abundant sources of information about Adam weren’t in any articles about his life but in those that touched on his death in 2004 – his obituaries. For the most part these seemed to spring from his family connection to Princess Diana:

Open verdict on relative of Diana (Guardian)

Coroner queries overdose verdict on death of Diana’s wayward stepbrother (Independent)

Death of Diana’s step-brother remains a mystery (Telegraph)

And so on. Obituaries that helped fill in some small biographical details and that varied from presenting the dried out details of his death to creating a sordid verbal diorama of it. It was the coupling of the family’s tragedies that most interested the media.

The details of Adam’s death, as outlined in these obituaries, are as sad as they are inconclusive: a room in the red light district of Phnom Penh, his dead, naked body surrounded by packets of viagra and other medications, suspicions of suicide, alcohol, cocaine and morphine in the blood, heart failure, erratic behaviour and more. More that just builds on the suggestions of dissolution, pain and sadness. He was edging on fifty years old. There had been drug and alcohol problems for years. Health issues. And unhappiness. Whatever caused his death it was a lonely way to go.

Adam wrote. Whether as a ‘wastrel’ he took this seriously I don’t know but suspect that he did – perhaps a languorous fight between literary ambition and the pursuit of pleasure that could only end in frustration and self-abasement given the brilliant and successful circle of literati that he moved in. He wrote one book published in 1984, ‘Happy Trails‘. I tracked it down in a second hand bookshop – a short and strange tale springing from the wellhead of his privileged background. Shards of Brideshead Revisited and the dust of Wodehouse, Chesterton and Maugham. I could find no reviews of his book. That he wrote, completed and published it is both a sign that perhaps the wastrel was not always on top in his inner struggles. His second book, never found a publisher. That disappointment may have, according to one obituary, contributed to his mental state at the time of his death.

I have to stop here. Not because I don’t have more on Adam but because ‘more’ is becoming exceedingly ‘less’.

My search has taken me to a place of disappointment, sadness, solitariness. I think of one of my favorite Borges stories where a brilliant and beautiful young man, who is the center of attention at a party, entrances the party-goers with his witty conversation and dazzling personality but as he is leaves the party and is finally alone wishes that he were dead. There is something in Adam’s story of this.

The more information I find about Adam the further away I am getting. My vantage point may be changing as I gather the biographical scraps but the mystery of who Adam was only deepens. Like chasing a mirage, there is, I know, no resolution and no end-point. I will not find Adam, I can only hope to reconstruct some poor equivalence of him. An unfair exercise for him and a tipping into fiction for me.

Perhaps, in the end, I have simply returned to the beginning: for me there is, and can only be, the Adam of my childhood and there I must leave him happily making toy weapons and reading Commando comics.